Artificial Intelligence 6001, Winter '26

Course Diary (Wareham)

Copyright 2026 by H.T. Wareham

All rights reserved

Week 1,

Week 2,

Week 3,

(In-class Exam Notes),

Week 4,

(end of diary)

Wednesday, January 28 (Lecture #1)

(FS)

[Class Notes]

- Introduction: What is Natural Language?

- A natural language is any language (be it spoken,

signed, or written) used by human beings to communicate

with each other, cf. artificial languages used to program

computers.

- There are ~7000 natural languages, with ~20 these languages,

e.g., Mandarin, Spanish, English, Hindi, and Arabic, being

spoken by more than 1% of the world's population.

- Example: The natural languages spoken by students in this course.

- Human language allows a complexity of expression and meaning

that has to date not been seen in linguistic behaviour

in animals, e.g., bird calls,, primate vocalizations, bee

dances, which are more akin to lists of codewords

with specific meanings that are not combined, e.g.,

"danger", "(this way to) food".

- Gorilla ASL experiments suggest that it is not just

the lack of an appropriate vocal apparatus -- the

ability to combine words to form arbitrarily complex

expressions is simply not present in animals.

- Talking animals are for now firmly in the

domain of fiction (and comedy).

- Example: Not the Nine O'Clock News (1980): Gerald the Gorilla

(Link)

- The ability to acquire and effectively communicate with a natural language

is one of the major hallmarks of human intelligence and sentience;

those individuals who have for whatever reasons failed to develop

this ability are often considered subhuman, e.g.,

feral children (the Wild Boy of Aveyron), the deaf (Children of a

Lesser God, Helen Keller).

- Example: The Miracle Worker (1961) [excerpt]

- The ability to acquire and effectively communicate with a natural

language is thus one of the major hallmarks of true artificial intelligence.

- Introduction: What is Natural Language Processing (NLP)?

- NLP is the subfield of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

concerned with the computations underlying

the processing (recognition, generation, and

acquisition) of natural human language (be it

spoken, signed, or written).

- NLP is distinguished from (though closely related to)

the processing of artificial languages, e.g.,

computer languages, formal languages (regular,

context-free, context-sensitive, etc).

- NLP emerged in the early 1950's with the first

commercial computers; originally focused on

machine translation, but subsequently broadened

to include all natural-language related tasks

(J&M, Section 1.6; Kay (2003); see also BKL,

Section 1.5 and Afterword).

- Two flavors of NLP: strong and narrow

- The focus of Strong NLP is on discovering

and implementing human-level language abilities

using approximately

the same mechanisms as human beings when

they communicate; as such, it is more

closely allied with classical linguistics

(and hence often goes by the name

"computational linguistics").

- The focus of Narrow NLP is on giving computers

human-level language abilities by whatever

means possible; as such, it is more closely

allied with AI (and is often referred to

by either "NLP" or more specific terms like "speech

processing").

- Narrow NLP is nonetheless influenced by Strong

NLP, and vice versa (to the extent that the

mechanisms proposed in Narrow NLP to get systems

up and running help to revise and make more

plausible the theories underlying Strong NLP).

- In this module, we will look at both types of

NLP, and distinguish them as necessary.

- Potential exam questions

- The Characteristics of Natural Language: Why Bother?

- Natural language is the area of study of linguistics.

Looking at what linguists have to say about the

characteristics of natural language is very valuable in

NLP for two reasons:

- Linguists have studied many languages and hence have

described and proposed mechanisms for handling

phenomena that may lie outside those handled by existing

NLP systems (many of which have been developed

to only handle English).

- Linguists have studied the full range of natural

processes, from sound perception to meaning, in

some cases for centuries (~2500 and 1300 years,

respectively, in the

case of Sanskrit and Arabic linguists), and have had

insights that may be invaluable in mitigating known

problems with existing NLP systems, e.g., Marcus and

Davis (2019, 2021).

- The Characteristics of Natural Language: Overview

- General model of language processing (adapted from

BKL, Figure 1.5):

- "A LangAct" is an utterance in spoken or

signed communication or a sentence in

written communication.

- The topmost left-to-right tier encodes

language recognition and the right-to-left

tier immediately below encodes language

production.

- The knowledge required to perform each step

(all of which must be acquired by a human

individual to use language) is the third tier,

and the lowest is the area

or areas of linguistics devoted to each

type of knowledge.

- Three language-related processes are thus encoded

in this diagram: recognition and production

(explicitly) and acquisition (implicitly).

- Whether one is modeling actual human language or implementing

language abilities in machines, the mechanisms underlying

each of language recognition, production, and acquisition

must be able to both (1) handle actual human language inputs and

outputs and (2) operate in a computationally efficient manner.

- As we will see over the course of this module, the

need to satisfy both of these criteria is one of

major explanations for how research has proceeded

(and diverged) in Strong and Narrow NLP.

- The Characteristics of Natural Language: Phonetics (J&M, Section 7)

- Phonetics is the study of the actual sounds produced in

human languages (phones), both from the

perspectives of

how they are produced by the human vocal

apparatus (articulatory phonetics) and

how they are characterized as sound waves

(acoustic phonetics).

- Acoustic phonetics is particularly important

in artificial speech analysis and synthesis.

- In many languages, the way words are written does

not correspond to the way sounds are pronounced

in those words, e.g.,

variation in pronouncing [t] (J&M, Table 7.9):

- aspirated (in initial position),

e.g., "toucan"

- unaspirated (after [s]),

e.g., "starfish"

- glottal stop (after vowel and before [n],

e.g., "kitten"

- tap (between vowels),

e.g., "butter"

The most common way of representing phones is to use

special sound-alphabets,

e.g., International Phonetic Alphabet

(IPA) [charts],

ARPAbet [Wikipedia]

(J&M, Table 7.1).

- Each language has its own characteristic repertoire of

sounds, and no natural language (let alone English)

uses the full range of possible sounds.

- Example: Xhosa tongue twisters (clicks)

- Even within a language, sounds can vary depending on their context, due to

constraints on the way articulators can move in

the vocal tract when progressing between adjacent

sounds (both within and between words) in an utterance.

- word-final [t]/[d] palatalization (J&M, Table 7.10),

e.g., "set your", "not yet", "did you"

- Word-final [t]/[d] deletion (J&M, Table 7.10)

e.g., "find him", "and we", "draft the"

- Variation in sounds can also depend on a variety of

other factors, e.g., rate of speech, word

frequency, speaker's state of mind / gender /

class / geographical location (J&M, Section 7.3.3).

- As if all this wasn't bad enough, it is often very

difficult to isolate individual sounds and words

from acoustic speech signals

Friday, January 30 (Lecture #2)

(FS)

[Class Notes]

- The Characteristics of Natural Language: Phonology (Bird (2003))

(Youtube)

- Phonology is the study of the systematic and

allowable ways in which sounds are realized

and can occur together in human languages.

- Each language has its own set of

semantically-indistinguishable

sound-variants, e.g., [pat] and [p^hat] are the

same word in English but different words in Hindi.

These semantically-indistinguishable variants of a sound

in a language are grouped together as phonemes.

- Variation in how phonemes are realized

as phones is often systematic, e.g., formation

of plurals in English:

| mop | mops | [s] |

| pot | pots | [s] |

| pick | picks | [s] |

| kiss | kisses | [(e)s] |

| mob | mobs | [z] |

| pod | pods | [z] |

| pig | pigs | [z] |

| pita | pitas | [z] |

| razz | razzes | [(e)z] |

Note that the phonetic form of the plural-morpheme /s/ is

a function of the last sound (and in particular, the

voicing of the last sound) in the word being pluralized.

A similar voicing of /s/ often (but not always) occurs

between vowels, e.g., "Stasi" vs. "Streisand".

- Such systematicity may involve non-adjacent sounds,

e.g., vowel harmony in the formation of plurals in Turkish (Kenstowicz (1994),

p. 25):

| dal | dallar | ``branch'' |

| kol | kollar | ``arm'' |

| kul | kullar | ``slave'' |

| yel | yeller | ``wind'' |

| dis | disler | ``tooth'' |

| g"ul | g"uller | ``race'' |

The form of the vowel in the plural-morpheme /lar/ is

a function of the vowel in the word being pluralized.

- It is tempting to think that such variation is encoded

in the lexicon, such that each possible form of a word

and its pronunciation are stored. However, such

variation is typically productive wrt new words (e.g.,

nonsense words, loanwords), which suggests that variation

is instead the result of processes that transform abstract

underlying lexical forms to concrete surface

pronounced forms.

- Plural of nonsense words in English, e.g.,

blicket / blickets, farg / fargs, klis / klisses.

- Unlimited concatenated morpheme vowel Harmony

in Turkish (Sproat (1992), p. 44):

c"opl"uklerimizdekilerdenmiydi =>

c"op + l"uk + ler + imiz + de + ki

+ ler + den + mi + y + di

``was it from those that were in our garbage cans?''

In Turkish, complete utterances can consist of a single

word in which the subject of the utterance is

a root-morpheme (in this case, [c"op], "garbage")

and all other (usually syntactic, in languages

like English) relations are indicated by

suffix-morphemes. As noted above, the vowels

in the suffix morphemes are all subject to

vowel harmony. Given the in principle unbounded

number of possible word-utterance in Turkish,

it is impossible to store them (let alone their

versions as modified by vowel harmony) in a

lexicon.

- Variation in English [r] according

Cantonese phonology in Chinenglish

(Demers and Farmer (1991), Exercise 3.10):

- [r] deletion (before consonant or final

sound in word), e.g., "tart", "party",

"guitar", "bar", "sergeant" (see also Boston English)

- [r] pronounced as [l] (before a vowel), e.g.

"strawberry","brandy", "aspirin", "Listerine",

"curry".

These rules can also hold when a Cantonese speaker

writes English text, e.g., "Phone Let Kloss."

- Modification of English loanwords in Japanese

(Lovins (1973)):

| dosutoru | ``duster'' |

| sutoroberri` | `strawberry'' |

| kurippaa` | `clippers'' |

| sutoraiki | ``strike'' |

| katsuretsu | ``cutlet'' |

| parusu | ``pulse'' |

| gurafu | ``graph'' |

Japanese has a single phoneme /r/ for the

liquid-phones [l] and [r]; moreover, it also

allows only very restricted types of

multi-consonant clusters. Hence, when words that

violate these constraints are borrowed from another

language, those words are changed

by the modification to [r] or

deletion of [l] and the insertion of vowels to break

up invalid multi-consonant clusters.

- Each language has its own phonology, which consists of

the phonemes of that language, constraints on

allowable sequences of phonemes (phonotactics),

and descriptions of how phonemes are instantiated as

phones in particular contexts.

The systematicities

within a language's phonology must be consistent with

(but are by no means limited to those dictated solely

by) vocal-tract articulator physics, e.g.,

consonant clusters in Japanese.

- Courtesy of underlying phonological representations

and processes, one is never sure if an observed

phonetic representation corresponds directly to the

underlying representation or is some process-mediated

modification of that representation, e.g.,

we are never sure if an observed phone corresponds to

an "identical" phoneme in the underlying representation.

This introduces one type of ambiguity into natural language

processing.

- The Characteristics of Natural Language: Morphology

(Trost (2003); Sproat (1992), Chapter 2)

- Morphology is the study of the systematic and

allowable ways in which symbol-string/meaning pieces

are organized into words in human languages.

- A symbol-string/meaning-piece is

called a morpheme.

- Two broad classes of morphemes: roots and affixes.

- A root is a morpheme that can exist alone as word or

is the meaning-core of a word, e.g., tree (noun),

walk (verb), bright (adjective).

- An affix is a morpheme that cannot exist independently

as a word, and only appears in language as part of word,

e.g., -s (plural), -ed (past tense; 3rd person),

-ness (nominalizer).

- A word is essentially a root combined with zero or more affixes.

Depending on the type of root, the affixes perform particular

functions, e.g., affixes mark plurals in nouns and

subject number and tense in verbs in English.

- Morphemes are language-specific and are stored in a language's

lexicon. The morphology of a language consists

of a lexicon and a specification of how morphemes are combined

to form words (morphotactics).

- Morpheme order typically matters, e.g.,

uncommonly, commonunly*, unlycommon* (English)

- There are a number of ways in which roots and affixes can be

combined in human languages (Trost (2003), Sections 2.4.2

and 2.4.3):

- Prefix: An affix attached to the front of the

root, e.g.,, the negative marker un- for

adjectives in English (uncommon, infeasible,

immature).

- Suffix: An affix attached to the back of the

root, e.g.,, the plural marker -s for

nouns in English (pots, pods, dishes).

- Circumfix: A prefix-suffix pair that must both

attach to the root, e.g.,, the past participle

marker ge-/-t for verbs in German

(gesagt "said", gelaufen "ran").

- Infix: An affix inserted at a specific position in

a root, e.g., the -um- verbalizer for nouns

and adjectives in Bontoc (Philippines):

| /fikas/ | "strong" |

/fumikas/ | "to be strong" |

| /kilad/ | "red" |

/kumilad/ | "to be red" |

| /fusl/ | "enemy" |

/fumusl/ | "to be an enemy" |

- Template Infix: An affix consisting of a sequence

of elements that are inserted at specific positions

into a root (root-and-template morphology),

e.g., active and passive markers -a-a- and

-u-i- for the root ktb ("write") in Arabic:

| katab | kutib | "to write" |

| kattab | kuttib | "cause to write" |

| ka:tab | ku:tib | "correspond" |

| taka:tab | tuku:tib | "write each other" |

- Reduplication: An affix consisting of a whole or

partial copy of the root that can be prefix, infix, or

suffix to the root, e.g., formation of the

habitual-repetitive in Javanese:

| /adus/ |

"take a bath" |

/odasadus/ |

| /bali/ |

"return" |

/bolabali/ |

| /bozen/ |

"tired of" |

/bozanbozen/ |

| /dolan/ |

"recreate" |

/dolandolen/ |

- As with phonological variation, there are several lines of

evidence which suggest that morphological variation is not

purely stored in the lexicon but rather the result of processes

operating on underlying forms:

- Productive morphological combination simulating complete

utterances in

words, e.g., Turkish example above.

- Morphology operating over new words in a language,

e.g., blicket -> blickets, television -> televise

-> televised / televising, barbacoa (Spanish) ->

barbecue (English) -> barbecues.

- As if all this didn't make things difficult enough, different

morphemes need not have different surface forms,

e.g, variants of "book"

"Where is my book?" (noun)

"I will book our vacation." (verb: to arrange)

"He doth book no argument in this matter, Milord." (verb: to tolerate)

- Courtesy of phonological transformations operating both

within and between morphemes and the non-uniqueness

of surface forms noted above, one is never sure if an observed

surface representation corresponds directly to the

underlying representation or is a modification of that

representation, e.g., is [blints] the plural of

"blint" or does it refer to a traditional Jewish cheese-stuffed

pancake? This introduces another type of ambiguity into natural

language processing.

- The Characteristics of Natural Language: Syntax (BKL, Section 8;

J&M, Chapter 12; Kaplan (2003))

Monday, February 2

- University closed; class cancelled.

Wednesday, February 4 (Lecture #3)

(FS)

[Class Notes]

- The Characteristics of Natural Language: Semantics, Discourse, and

Pragmatics (Lappin (2003); Leech and Weisser (2003); Ramsay (2003))

- Semantics is the study of the manner in which meaning is

associated with utterances in human language;

discourse and pragmatics focus, respectively, on how meaning

is maintained and modified over the course of multi-person

dialogues and how these people chose different

individual-utterance and dialogue styles to communicate

effectively.

- Meaning seems to be very closely related to syntactic

structure in individual utterances; however, the meaning

of an utterance can vary dramatically depending on the

spatio-temporal nature of the discourse and the goals

of the communicators, e.g., "It's cold outside."

(statement of fact spoken in Hawaii; statement of fact

spoken on the International Space Station; implicit order

to close window).

- Various mechanisms are used to maintain and direct focus within

an ongoing discourse (Ramsay (2003), Section 6.4):

- Different syntactic variants with subtly different

meanings, e.g., "Ralph stole my bike" vs

"My bike was stolen by Ralph".

- Different utterance intonation-emphasis, e.g.,

"I didn't steal your bike" vs "I didn't steal your BIKE"

vs "I didn't steal YOUR bike" vs "I didn't STEAL your bike".

- Syntactic variants which presuppose a particular

premise, e.g., "How long have you been beating

your wife?"

- Syntactic variants which imply something by not

explicitly mentioning it, e.g.,

"Some people left the party at midnight" (-> and

some of them didn't), "I believe that she loves me"

(-> but I'm not sure that she does).

- Another mechanism for structuring discourse is to use

references (anaphora) to previously discussed

entities (Mitkov (2003a)).

- There are many kinds of anaphora (Mitkov (2003a),

Section 14.1.2):

- Pronominal anaphora, e.g.,

"A knee jerked between Ralph's legs and he fell

sideways busying himself with his pain as the

fight rolled over him."

- Adverb anaphora, e.g., "We shall

go to McDonald's and meet you there."

- Zero anaphora, e.g., "Amy looked

at her test score but was disappointed with the

results."

- Though a convenient conversational shorthand, anaphora can

be (if not carefully used) ambiguous, e.g.,

"The man stared at the male wolf. He salivated at the

thought of his next meal."

"Place part A on Assembly B. Slide it to the right."

"Put the doohickey by the whatchamacallit over there."

- As demonstrated above, utterance meaning depends not only the

individual utterances, but on the context in which those

utterance occur (including

knowledge of both the past utterances in a dialogue and

the possibly unknown and dynamic goals and knowledge of all

participants in the discourse), which adds yet another

layer of ambiguity into natural language processing ...

- It seems then that natural language, by virtue of its structure

and use, encodes both a lot of ambiguity and variation, as well

as a wide variety of structures at all levels.

- There is a final set of computational characteristics

of natural language that must be either accommodated (in the

case of strong NLP systems) or circumvented by clever means (in

the case of narrow NLP systems).

- The Characteristics of Natural Language: Natural Language

Operation and Acquisition

- Human beings (both adults and children) use language effectively

with the aid of finite and

ultimately limited computational devices, e.g.,

our brains.

- Utterances are generated and comprehended relatively quickly

in most everyday situations, cf., bad telephone

connections active construction sites.

- Generation and performance acquisition degrades more or

less gracefully with the increasing complexity and length

of utterances.

- Example: Prototypical natural language acquisition device

- Given exposure to a human language, any child can acquire

the phonological, morphological, and semantic (if not total

lexical) knowledge of that language within four to seven years.

- This exposure does not need to be simplified, cf.,

Motherese.

- This exposure does not need to be comprehensive or

exhaustive, with many examples of each possible

phenomena in the language.

- Individual utterances in this exposure need not be

either grammatical or have their grammaticality-status

stated.

- Produced utterances by the child need not be assessed

for grammaticality or corrected.

- Given exposure to any human language, any human being can

acquire that language, and children under the age of 10 years

are superbly good at this. In addition:

- If children are exposed to two distinct

language simultaneously, they will acquire both

languages, i.e., they will become bilingual.

- If children are exposed to a pidgin created by

combining elements of two or more languages, they

will regularize the unsystematic parts of the pidgin

to create a proper hybrid language (creole).

- Given all the characteristics of natural language discussed in the

previous lectures and their explicit and implied

constraints on what an NLP system must do, what then are appropriate

computational mechanisms for implementing NLP systems? It is

appropriate to consider first what linguists, the folk who have been

studying natural language for the longest time, have to say on this

matter.

- NLP Mechanisms: The View from Linguistics

- Three basic types of mechanisms are required to implement

NLP:

- Sequences (to represent linguistic signals at

various levels of processing).

- Sets (to represent sets of linguistic entities,

e.g., lexicons)

- Processes (to implement proposed linguistic

processes operating both between and within

levels of processing).

- Given that linguistic signals are expressed as

temporal (acoustic and signed speech) and spatial

(written sequences) sequences of elements, there must be

a way of representing such sequences.

- Sequence elements can be atomic (e.g., symbols)

or have their own internal structure (e.g.,

feature matrices (phones / phonemes), form-meaning bundles

(morphemes)); for simplicity, assume

for now that elements are symbols.

- There are at least two types of such sequences

representing underlying and surface forms.

- Where necessary, hierarchical levels of

structure such as syntactic parse trees can be encoded

as sequences by using appropriate interpolated and nested

brackets, e.g., "[[the quick brown fox] [[jumped

over] [the lazy brown dog]]]"

- The existence of lexicons implies mechanisms for

representing sets of element-sequences, as well

as accessing and modifying the members of those sets.

- The various processes operating between underlying and

surface forms presuppose mechanisms implementing those

processes.

- The most popular implementation of processes is as

rules that specify transformations of one form

to another form, e.g., add voice

to the noun-final plural morpheme /s/ if

the last sound in the noun is voiced.

- Rules are applied in a specified

order to transform an underlying form to its

associated surface form for utterance production,

and in reverse fashion to transform a surface form to

its associated underlying form(s) for utterance

comprehension (ambiguity creating

the possibility of multiple such associated forms).

- Rules can be viewed as functions. Given the various

types of ambiguity we have seen, these functions are

at least one-many.

- In each linguistic level, the functions corresponding

to individual rules can be composed in rule application

order to create "master" functions that transform

between representations on adjacent linguistic levels, e.g.,

In this diagram, the inverse of function X() is

written as X-().

- The above corresponds to classical appproaches to NLP;

alternatively, natural language can be seen as a single

function that is the composition of all of these

individual level-functions or their inverses, e.g.,

for meaning m and utterance u, uttterance

generation is u = G(m) = P2(P1(M(S(m)))))

and utterance comprehension is

m = C(u) = S-(M-(P2-(P1-(u))))).

- This alternative is that taken by many neural

network implementations of NLP (which will be

discussed later in this module).

- Some such systems like ChatGPT go further by

going directly from utterances to replies, e.g.,

u' = R(u) = P2(P1(M(S(S-(M-(P2-(P1-(u))))).

This raises the question if such systems ever

actually compute (even internally) meanings associated with

utterances at all, cf. Hinton's "Thought Vectors"

(see notes on Encoders/Decoders below).

- Great care must be taken in establishing what parameters

are necessary as input to these functions and that such

parameters are available. For example, a syntax

function can get by with a morphological analysis

of an utterance, but a semantics function would seem

to require as input not only possible syntactic

analyses of an utterance but also discourse context

and models of discourse participant knowledge and

intentions.

- Following practice in linguistics, we can assume that all

natural language processes operate in a deterministic

fashion. However, given the complexity of proposed processes

and how they may interact, it may be useful as an

intermediate stage in analyzing linguistic complexity to

allow mechanisms that operate probabilistically,

e.g., rules that have a specified probability of

application, composed systems of rules that rank one-many

outputs by their probability of occurrence.

- This is analogous to the use of statistical mechanics to

summarize and analyze the overall behavior of large

groups of particles in physics.

- Such mechanisms may be analysis end-points

in themselves if it turns out that either the

interaction of deterministic linguistic processes is

too complex to untangle or there are genuinely

probabilistic processes

underlying natural language processing in humans.

- Beware of over-simplification for the sake of

engineering convenience and equating the model with

the phenomena, e.g., complex deterministic one-many ->

simplified probabilistic one-many -> simplified

probabilistic one-one / most probable (the last of

which is what neural-network-based NLP systems do).

- Potential exam questions

Friday, February 6 (Lecture #4)

(FS)

[Class Notes]

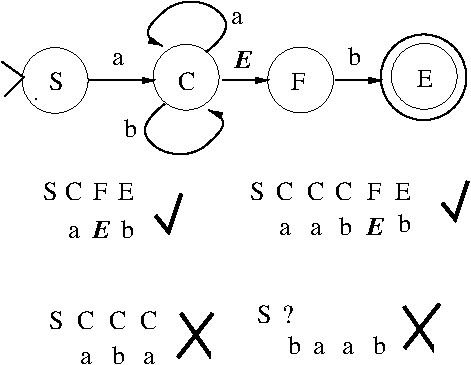

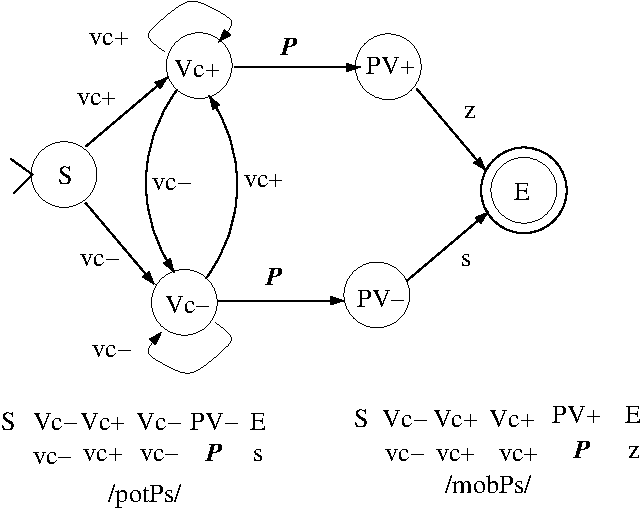

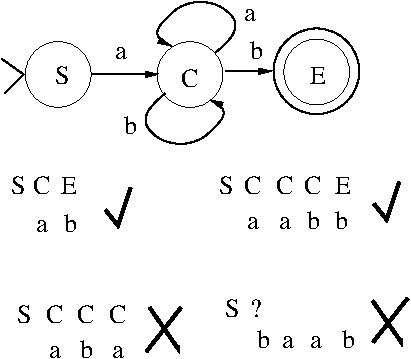

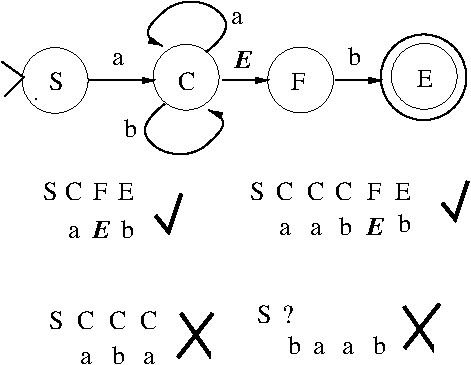

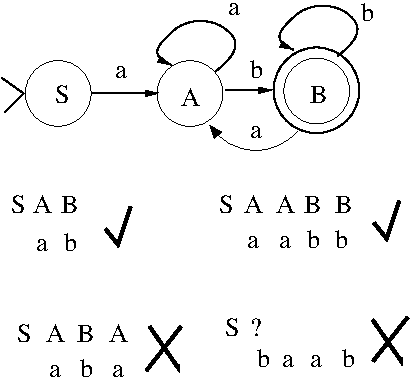

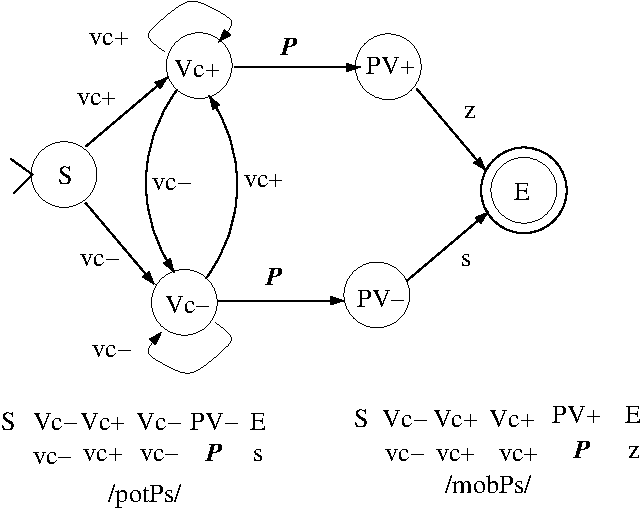

- NLP Mechanisms: Finite-state automata (FSA) (Martin-Vide (2003), Section 8.3.1;

Nederhof (1996); Roche and Schabes (1997a), Section 1.2)

- Originated in the Engineering community; inspired by

the discrete finite neuron model proposed by

McCullough and Pitts in 1943.

- Basic Terminology: (start / finish) state,

(symbol-labeled) transition, acceptance.

- Operation: generation / recognition of strings

- Generation builds a string from left to right, adding

symbols to the right-hand end of the string as one

progresses along a transition-path from the start

state to a final state.

- Recognition steps through a string from left to right,

deleting symbols from the left-hand end of the string

as one progresses along a transition-path from the

start state to a final state.

- Note that one need only keep track of one FSA-state

during both operations described above, namely, the

last state visited.

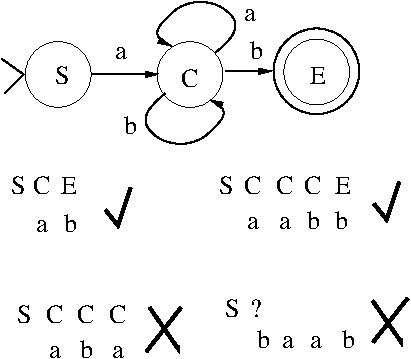

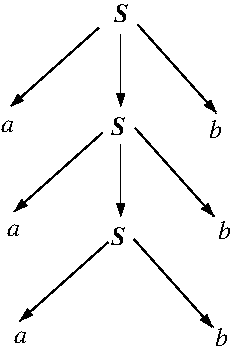

- Example #1: A DFA for the set

of all strings over the alphabet {a,b} that

consist of one or more concatenated copies of ab.

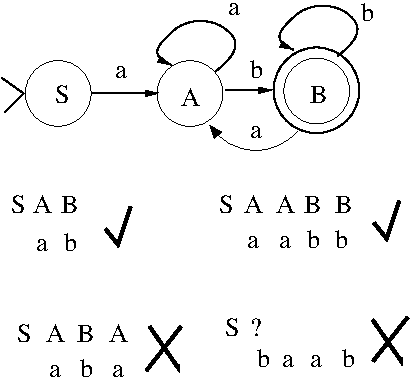

- Types of FSA:

- Deterministic (DFA): At each state and for

each symbol in the alphabet, there is at most

one transition from that state labeled with

that symbol.

- Non-Deterministic (NFA): At each state, there

may be more than one transition from that

state labeled with a particular symbol and/or

there may be transitions labeled with special

symbol epsilon (denoted in our diagrams by

symbol E).

- Revised notion of string acceptance: see

if there is any path through the

NFA that accepts the input string.

- Example #2: An NFA for the set

of all strings over the alphabet {a,b} that

start with an a and end with a b (uses

multiple same-label outward transitions).

- DFA can recognize strings in time linear in the

length of the input string, but may not be

compact; NFA are compact but may require

time exponential in the length of a string to

recognize that string (need to follow all

possible computational paths to check string

acceptance).

- Example #3: An NFA for the set

of all strings over the alphabet {a,b} that

start with an a and end with a b (uses

epsilon-transitions).

- Oddly enough, deterministic and non-deterministic

FSA are equivalent in recognition power, i.e.,

there is a DFA for a particular set of strings iff

there is an NFA for that set of strings.

- Example #4: A DFA for the set

of all strings over the alphabet {a,b} that

start with an a and end with a b.

- There are a variety of operations for combining pairs of

finite-state automata into a single automaton, e.g.,

concatenation, union, intersection.

- Application: Building lexicons

- The simplest types of lexicons are lists of

morphemes which, for each morpheme, store the

surface form and syntactic / semantic

information associated with that morpheme.

- A list of surface forms can be stored as FSA in two ways:

- DFA encoding of a trie (= retrieval tree)

- Deterministic acyclic finite automaton (DAFA)

One creates a trie by compacting a word-list and a DAFA

for a word-list by compacting a trie-DFA for that

word-list.

- Example #5: A trie-DFA

encoding the lexicon {"in", "inline", "input", "our",

"out", "outline", "output"}.

- Example #6: A DAFA

encoding the lexicon {"in", "inline", "input", "our",

"out", "outline", "output"}.

- Application: Implementing morphotactics

- More complex lexicons need to take into account how

morphemes are combined to form words.

- Example #7: A DFA implementing the

constraint that the voicing of the

noun-final plural morpheme must match the

voicing of the final sound in the noun being

pluralized.

- The simplest types of purely concatenative morphotactics

can be encoded as a finite-state manner by indicating

for each morpheme-type sublexicon which types of

morphemes can precede and follow morphemes in

that sublexicon, e.g., nouns precede

pluralization-morphemes in English.

- More complex morphotactics, e.g., circumfixes,

infixes, reduplication, can be layered on top of

lexicon FSA using additional mechanisms

(Beesley and Karttunen (2000); Beesley and Karttunen

(2003), Chapter 8; Kiraz (2000)).

- NLP Mechanisms: Finite-state transducers (FST) (J&M, Section 3.4, Mohri (1997);

Roche and Schabes (1997a), Section 1.3)

- Generalization of FSA in which each transition is

labeled with a symbol-pair (either or both of

which may be the special symbol epsilon).

- The first symbol in each pair is called the lower

symbol and the second is called the upper symbol.

- The alphabet of all lower-symbols in an FST need

not have a non-empty intersection with the alphabet

of all upper-symbols in an FST.

- Example #8: An FST for transforming

between the set

of all strings over the alphabet {a,b} that consist of

n, n >= 0, concatenated copies of ab and the set

of all strings over the alphabet {c,d} that

consist of n, n >= 0, concatenated copies of cd.

- Operation: generation / recognition of string-pairs,

reconstruction of upper (lower) string associated

with given lower (upper) string.

- Generation of a string-pair builds that pair from left

to right, adding symbol-pairs to the right-hand end of

the string-pair as one progresses along a

transition-path from the start state to a

final state.

- Recognition of a string-pair proceeds by stepping

through that pair from left to right, deleting

symbol-pairs from the left-hand end of the string-pair

as one progresses along a transition-path from the

start state to a final state.

- Reconstruction of a string-pair associated with a given

string builds the missing string of the pair from left

to right, adding missing-string symbols to the

right-hand end of the missing string as one progresses

along a transition-path from the start state to a

final state in accordance with the given string.

- As the given string may be either the lower or

upper string, there

are two types of string-pair reconstructions.

- Each reconstructed string-pair corresponds to a

particular

path through the FST guided by the given string.

- Depending on the structure of the FST, there may

be more than one path through the FST consistent

with the given string, and hence more than

one string-pair reconstruction.

- Note that one need only keep track of one FST-state

during all operations described above, namely, the

last state visited.

- Unlike FSA, there are many types of FST and many types

of FST (non-)determinism.

- Example #9: An FST for transforming

between the set

of all strings over the alphabet {a,b} that consist of

n, n >= 0, concatenated copies of ab and the set

of all strings over the alphabet {a,b} that

consist of n, n >= 0, concatenated copies of aba.

- There are a variety of operations for combining pairs of

finite-state transducers into a single transducer, e.g.,

composition, intersection.

- Application: Implementing rule-based systems

- Many types of linguistic rules can

be implemented as FST.

- Example #10: An FST implementing the

rule that voice be added to the noun-final plural morpheme

/s/ if the last sound in the noun is voiced.

- The sequential application

of rules can be simulated using the FST created by the

sequential composition (in the specified order) of the FST

corresponding to the rules.

- Application: Implementing lexical transducers (Beesley and

Karttunen (2003), Section 1.8)

- A lexicon FSA can be converted into an FST by

replacing each transition-label x with x:x,

e.g., the identity FST associated an FSA.

This lexicon FST can then be composed with the

the underlying / surface transformation FST

encoding a constraint- or rule-based

morphonological system to create a lexical

transducer.

- Note as FST are bidirectional, so are lexical

transducers; hence, can reconstruct surface or

lexical forms from given lexical or surface

forms with equal ease.

- Potential exam questions

Monday, February 9 (Lecture #5)

(FS)

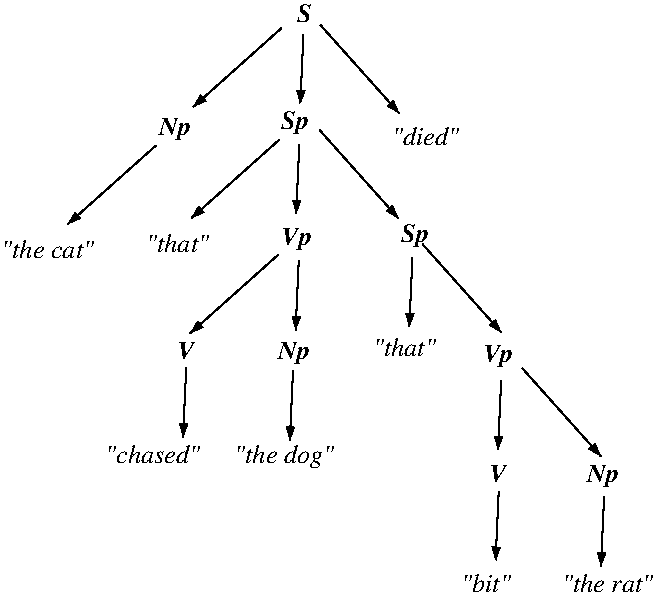

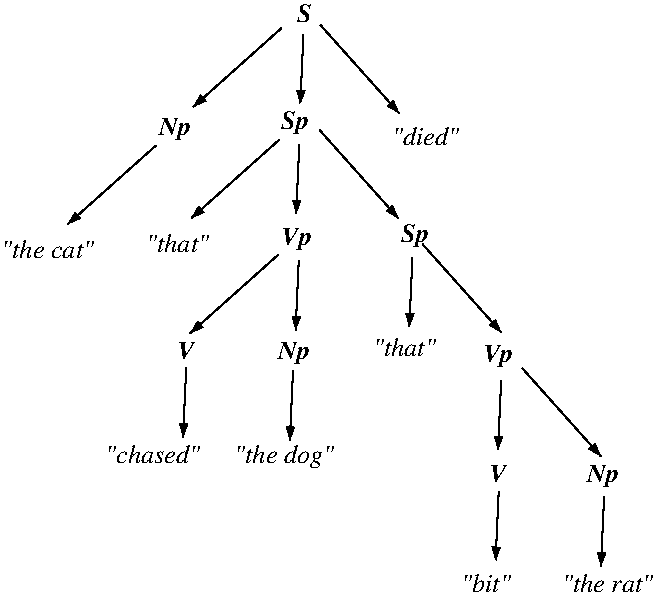

Example #3: A CFG for an infinite-size subset of

all garden-path utterances, e.g., "The cat that

chased the dog that bit the rat died.":

S -> Np Sp "died" | NP "died"

Np -> "the cat" | "the dog" | "the rat" | "the elephant"

Sp -> that" Vp Sp | "that" Vp

Vp -> V Np

V -> "admired" | "bit" | "chased"

Example #4: A CFG for an infinite-size subset of

the set of all recursively-embedded utterances.

S -> Np Sp "likes tuna fish" | Np "likes tuna fish"

Np -> "the cat" | "the dog" | "the rat" | "the elephant"

Sp -> Np Sp V | Np V

V -> "admired" | "bit" | "chased"

Example #5: A CFG for an infinite-size subset of

the set of all utterances, e.g. "the dog saw a man in the park"

(BKL, pp. 298-299).

S -> Np Vp

Np -> "John" | "Mary" | "Bob" | Det N | Det N Pp

Det -> "the" | "my"

N -> "man" | "dog" | "cat" | "telescope" | "park"

Pp -> P Np

P -> "in" | "on" | "by" | "with"

Vp -> V Np | V Np Pp

Unlike the other sample grammars above, this grammar

is structurally ambiguous because there may be more than

one parse for certain utterances involving prepositional

phrases (Pp) as it is not obvious which noun phrase (Np)

a Pp is attached to, e.g., in "the dog saw the

man in the park", is the man (above) or the dog (below)

in the park?

Note that the parse trees encode grammatical relations between

entities in the utterances, and that these relations have

associated semantics; hence, one can use parse trees as encodings

of basic utterance meaning!

- As shown in Example #5 above, parse trees via structural

ambiguity can nicely encode semantic ambiguity.

Context-free mechanisms can handle many complex linguistic

phenomena like unbounded numbers of recursively-embedded

long-distance dependencies. This done by parsing, which

both recognizes and adds an internal hierarchical

constituent phrase-structure of a sentence.

- Parsing a sentence S with n words relative to a grammar G can be

seen as a

search over all possible parse trees that can be generated

by grammar G with the goal of finding all parse trees

whose leaves are labelled with exactly the words in S in an

order that (depending on the language, is either exactly or

is consistent with) that in S.

Though some algorithms implement the generation of one

valid parse for a given sentence much quicker than

others, the generation of all valid search trees

(which is required in the simplest human-guided schemes

for resolving sentence ambiguities) for all parsing

algorithms is in the worst case at least the number of

valid parse trees for the given sentence S relative

to the given grammar G.

- There are natural grammars for which this is

quantity is exponential in the number of words

in the given sentence (BKL, p. 317; Carpenter (2003),

Section 9.4.2).

Dealing with very large numbers of output

derivation-trees is problematic. What can be done? Can

deal with this by using probability -- that is, by only

computing the derivation-tree with highest probability for

the given utterance!

This is a general way to handle the many-results problem

with ambiguous linguistic processes. There are many

models of probabilistic computing with context-free

grammars and finite-state automata and transducers,

and many of these were state-of-the-art for NLP for

several decades. However, as Li (2022) points out, the

more purely mathematical probabilistic modeling of

natural language started over a century ago with

Markov Models is actually the research tradition that

leads to the final NLP implementation mechanism we shall

examine -- namely, (artificial) neural networks.

Potential exam questions

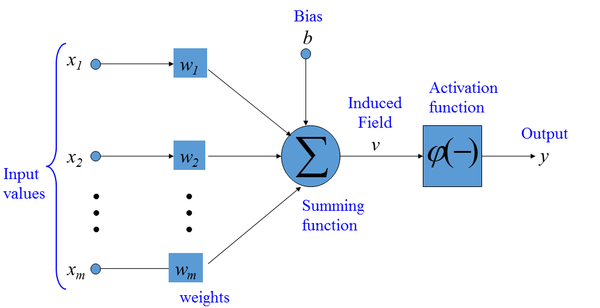

NLP Mechanisms: Neural Networks (Kedia and Rasu (2020), Chapters 8-11)

- The finite-state and context-free NLP mechanisms we have studied thus

far in the module are all process-oriented, as they all implement

rules (explicitly in the case of grammars, implicitly via the

state-transitions in automata and transducers) that correspond to

processes postulated by linguists on the basis of observed

human utterances.

- Neural network (NN) NLP mechanisms, in contrast, are

function-oriented, in that the components of these mechanisms typically

do not have linguistic-postulated correlates and the focus is instead

on inferring (with the assistance of massive amounts of observed

human utterances) various functions associated with NLP.

- These functions map linguistic sequences onto categories, e.g.,

spam e-mail detection, sentiment analysis, or other linguistic

sequences, e.g., Part-of-Speech (PoS) tagging, chatbot

responses, machine translation between human languages.

- In many cases, these linguistic sequences are recodings of

human utterances in terms of multi-dimensional numerical

vectors or matrices. There a variety of methods for creating

these vectors and matrices, e.g., bag of words, n-grams,

word / sentence / document embeddings (Kedia and Rasu (2020),

Chapters 4-6; Vajjala et al (2020), Chapter 3).

- Neural network research can be characterized to date in three waves:

- First Wave (1943-1968): McCulloch and Pitts propose abstract

neurons in 1943. Starting in the late 1950s, Rosenblatt explores the

possibilities for representing and learning functions relative

to single abstract neurons (which he calls perceptrons).

The mathematical principles underlying the

back propagation procedure for training neural networks

are developed in the early 1960's (Section 5.5,

Schmidhuber (2015)). Perceptron research is killed off by the

publication in 1968 of Minsky

and Papert's monograph Perceptrons, in which they show

by rigorous mathematical proof that perceptrons are incapable

of representing many basic mathematical functions such as

Exclusive OR (XOR).

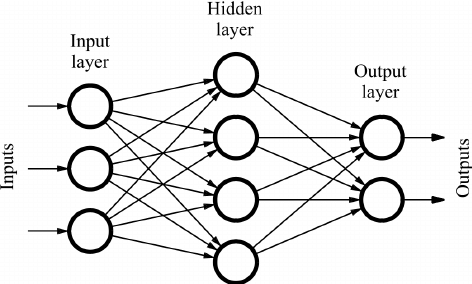

- Second Wave (1980-1990): Rumelhart, McClelland, and colleagues

propose and explore the possibilities for multi-level feed-forward

neural networks incorporating hidden layers of artificial

neurons. This is aided immensely by the (re)discovery

of the

backpropagation procedure, which allows efficient learning of

arbitrary functions by multi-layer neural networks. Though it is

shown that these networks are powerful (Universal Approximation

Theorems state that any well-behaved function can be approximated

to an arbitrarily close degree by a neural network with only one

hidden layer), research remains academic as backpropagation on

even small to moderate-size networks is too data- and

computation-intensive.

- It is during this period that NN-based NLP research flourishes,

taking up over a third of the second volume of the

1987 summary work Parallel Distributed Processing (PDP).

Alternatives to feed-forward NN (Recurrent Neural Networks

(see below)) for NLP are also explored by Elman starting

in 1990.

- Third Wave (2000-now): With the availability of massive amounts

of data and computational power courtesy of the Internet and

Moore's Law (as instantiated in special-purpose processors like

GPUs), neural network research re-ignites in a number of

areas, starting with image processing and computer vision. This

is aided by the development of neural networks incorporating

special structures inspired by structures in the human

brain, e.g., Convolutional Neural Networks, Long

Short-Term Memory cells (see below).

Starting around 2010, this wave reaches NLP; the results are

so spectacular that by 2018, NN-based NLP techniques are state of

the art in many applications.

- This is in large part because the more complex

types of neural networks have enabled the creation of

pre-trained NLP models that can subsequently be

customized with relatively little training data for

particular applications, e.g., question answering

systems (Li (2022)).

Wednesday, February 11 (Lecture #6)

(FS)

- NLP Mechanisms: Neural Networks (Kedia and Rasu (2020), Chapters 8-11) (Cont'd)

- Let us now explore this research specific to NLP by examining the

various types of neural networks that have emerged during these

three waves.

- Feed-forward Multi-layer Neural Networks (FF-NN) (Kedia and

Rasu (2020), Chapter 8)

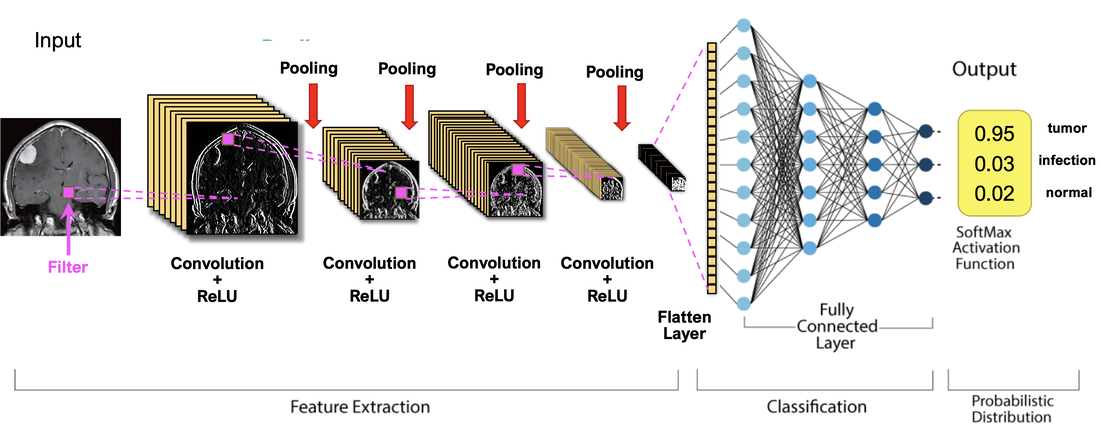

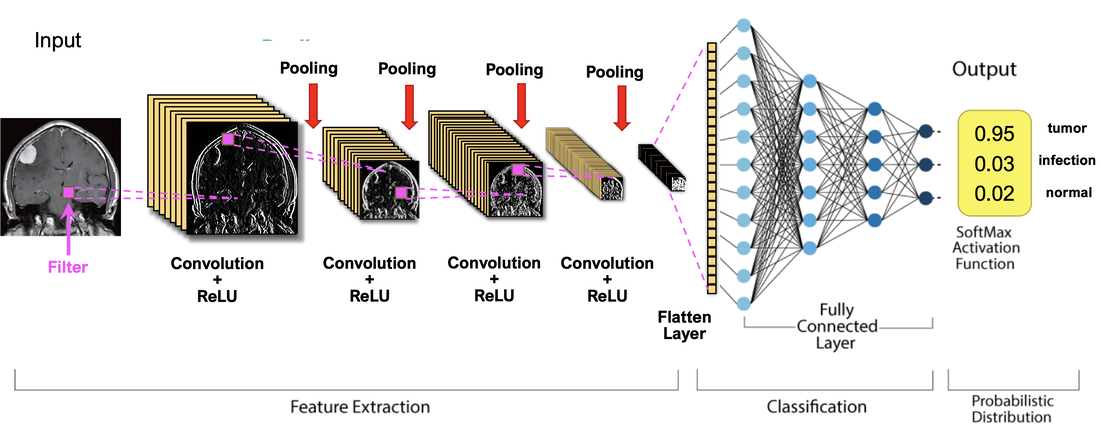

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) (Kedia and Rasu (2020), Chapter 9)

- First proposed for image processing and computer vision in

the late 1980's, by analogy with known neural structure

in the human visual cortex. CNN are designed to detect

and compute over spatial patterns formed by input elements

that are close together, e.g., lines / line

crossings / corners within images.

- A CNN consists of a series of feature detectors over a 2D

input field, followed by "pooling" layers that summarize

detected features and an FF-NN that takes the outputs of the

pooling layers as inputs.

- Patterns are encoded as small square filter matrices called

kernels, and pattern detection is implemented by

multiplying filter matrices by a version of the 2D

input matrix that is padded with zeroes on the right

and lower edges to ensure that the filter is applied

to all elements of the input matrix.

- Pooling of matrices produced by feature detection

summarizes non-overlapping blocks of values by

various techniques, e.g., block maximum /

average / sum; the resulting downsampling not only

reduces the amount of data input to the FF-NN but also

helps prevent overfitting.

- Though they have been successful in certain applications,

e.g., image classification, CNN are not good

at detecting long-distance sequence or temporal

relationships between input elements.

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) (Kedia and Rasu (2020), Chapter 10)

- RNN enable recognition and processing of temporal

relationships in sequences by gifting neural networks

with memory of past activities.

- An individual RNN cell is a FF-NN which produces an output

yt at time t using the input xt at time

t (that is, the element at position t in the

input sequence) and the hidden state h(t-1) of the

cell at time t-1.

- An RNN can be "unrolled" relative to its operation over time.

In this unrolled version, note that the FF-NNs in all timesteps

are identical.

- RNN can be trained by backpropagation that moves backwards in

time rather than layers from the output, where the initial

hidden state consists of random values. This is best

visualized relative in the unrolled version. That being said,

it is important to note that the only FF-NN whose weights

and biases are changed is that corresponding to timestep

zero -- in all other cells, only errors and gradients are

propagated.

- There are several types of RNN, each of which is used in

particular applications (shown below in their unrolled

versions). These types vary in the relationship

between the lengths of their input and output sequences.

- One-many RNN are good for generating narratives.

- Many-one RNN are good for implementing functions

over sequences, e.g., spam e-mail

detection, sentiment analysis.

- Many-many RNN are good for implementing

functions between same-length sequences,

e.g., PoS tagging, or different-length

sequences, e.g., machine translation.

- Though powerful, RNN are unfortunately deep networks as

input and output sequences can be long (particular in

NLP). Hence, they are particularly prone to the

exploding and vanishing gradient problems noted above.

Additional problems arise from the necessity of large

hidden states to process long sequences.

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Cells (Kedia and Rasu (2020),

Chapter 10)

- One can get the advantages of RNN wrt temporal processing

without many of the disadvantages introduced by extended

recurrent processing over time by replacing the RNN cells

in unrolled versions with LSTM cells.

- LSTM cells (first proposed in 1995) allow dramatic reductions in

the sizes of the

hidden states by allowing both the forgetting of older

irrelevant and the remembering of new relevant information.

- Each LSTM cell consists of an input-output-chained sequence

of three gates -- namely, a forget gate, an input gate, and

an output gate.

- In addition to dramatically reducing the required sizes

of hidden states, LSTM-based neural networks eliminate

the vanishing (and mitigate to a degree the exploding)

gradient problem because backpropagation training for

a particular cell only needs to take into account

the cells immediately before and after it in the LSTM-based

neural network.

- Encoders and Decoders (Kedia and Rasu (2020), Chapter 11)

- The encoder / decoder architecture, first proposed in 2014,

implements sequence-to-sequence functions (Seq2Seq) by

(1) building on the many-many RNN architecture, (2)

replacing RNN cells with LSTM cells, and (3) allowing more

structure in the hidden state passed from the final

encoder cell to the first decoder cell (context vector).

- Hinton has on at least one occasion proposed

that context vectors be considered "thought

vectors".

- In this architecture, the initial encoder hidden state

consists of random values and training focuses on the decoder

such that the training set consists of context vector /

target sequence pairs.

- The production of a target sentence by the decoder is

triggered by the input of a start token and

ended by the output of an end token.

- Fixed-length context vectors are problematic if target sequences

that must be produced by the decoder are longer than the

source sequences used to create context vectors in the encoder.

This has been mitigated by incorporating an attention mechanism

into the encoder / decoder architecture.

- In this mechanism, all (not just the final) hidden

states produced by the encoder are available to every cell

in the decoder.

- This set of hidden states is then weighted in a manner

specific to each decoder cell to indicate the relevance of

each encoder-input token to that cell's output token.

- Essentially, this enables decoder cells to have

individually-tailored variable-length context vectors.

- Transformers (Kedia and Rasu (2020), Chapter 11)

- The Transformer architecture, first proposed in 2017,

retains the notion of encoders and decoders but discards

the many-many RNN backbone. The encoders and decoders

are placed in an encoder stack and a decoder stack,

respectively.

- Starting 2018, Transformers have become the state-of-the-art

NLP techniques courtesy of two frameworks, BERT and GPT,

both of which pre-train generic Transformer-based systems for a specific language that can

subsequently by fine-tuned for particular applications.

- BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representation from

Transformers)

- Created at Google in 2018.

- Two versions: BERT_BASE (which uses 12 encoders) and

BERT_LARGE (which uses 24 encoders).

- Both trained on Internet corpus totalling

3.3 billion words.

- Code and training datasets are open-source.

- GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformers)

- Created at OpenAI in 2018.

- Four versions released so far (GPT-1, GPT-2, GPT-3, and

GPT-4); though initially open-source, by GPT-3

release, full code access is only available to

Microsoft employees and all others can only

see APIs.

- Also trained on massive (though proprietary) dataset;

though GPT-3 architecture details not known, has

175 billion trainable parameters, which is 500 times

larger than BERT's biggest version (Edwards (2021),

p. 9).

- Though very successful in some applications, e.g.,

question-answering systems and machine translation,

and on certain benchmarks, e.g., the Large-scale Reading

and Compression (RACE) tool for assessing high-school level

understanding of text, current Transformer-based NLP systems

produce nonsense in other situations, e.g., "a car has

four wheels" vs. "a car has

two round wheels" (Edwards (2021), p. 10). It is increasingly

being acknowledged that attention and self-attention are not

enough, and that some way must be found to integrate

world knowledge to improve performance (Reis et al (2021);

Edwards (2021); Marcus and Davis (2019, 2021); see

also below and Haigh (2023a, 2023b, 2024a, 2024b, 2025)).

Thursday, February 12

Friday, February 13 (Lecture #7)

(FS)

- NLP Mechanisms: Neural Networks (Kedia and Rasu (2020), Chapters 8-11) (Cont'd)

- Working with Neural Networks (Vajjala et al (2020), Chapter 1)

- In the eyes of some industry-oriented practitioners, rule- and NN-based

components have different roles over the lifetime of

modern NLP systems (Vajjala et al (2020), p. 18):

- Rule-based are excellent for constructing initial versions of

NLP systems before task-specific NLP data is available, and are

useful in delineating exactly what the system must do.

- Once (a large amount of) task-specific NLP data is available,

machine learning and NN-based components can be employed to

rapidly create better production-level systems.

- Given that systems created by machine-learning and NN-based

components make mistakes, these mistakes can be rectified as needed

in a mature production system by using rule-based component

"patches".

- That being said, NN-based systems are not yet the silver bullet for

NLP for a number of reasons (Vajjala et al (2020), pp. 28-31):

- Overfitting small datasets (With increasing number of

parameters comes increasing expressivity; hence, if

insufficient data is available, NN models will overfit and

not generalize well).

- Few-shot learning and synthetic data generation (Though

techniques have been developed in computer vision to allow

few-shot learning, no such techniques have been developed

relative to NLP).

- Domain adaptation (NN models trained on text from one domain,

e.g., internet texts and product reviews, may not

generalize to domains which are syntax- and

semantic-structure specific, e.g., law, healthcare. In those

situations, rule-based models explicitly encoding domain

knowledge will be preferable).

- Interpretable models (Unlike rule-based NLP systems, it is

often difficult to interpret why NN models behave as they do;

this is a requirement made by businesses).

- For example, though Transformer-based systems readily

associate words with context, it remains far from clear

what relationship is actually learned in training

("BERTology") (Edwards (2021), p. 10).

- Common sense and world knowledge (Current NN models may

perform well on standard benchmarks but are still not capable of

common sense understanding and logical reasoning. Both of these

require world knowledge, and attempts to integrate such

knowledge into NN-based NLP systems have not yet been successful).

- Cost (The data, specialized hardware, and lengthy computation

times required to both train and maintain over time large NN-based

NLP systems may be prohibitive for all but the largest businesses).

- On-device deployment (For applications that require NLP

systems to be embedded in small devices rather than the computing

cloud (e.g., internet-less simultaneous machine translation),

the memory- and computation-size of NN-based NLP systems may

not be practical).

Indeed, the above suggests that rule-based NLP systems may be much more

applicable than is sometimes thought, and that a fusion of NN- and

rule-based NLP system components (or a fundamental re-thinking of NLP

system architecture that incorporates the best features of both) may be

necessary to create the practical real-world NLP systems of the future.

- Potential exam questions

- Applications: Partial Morphological and Syntactic Parsing

- As we have seen in previous lectures, complete

morphological parsing of words can be done using

finite-state mechanisms and complete syntactic parsing of

utterances can be done using context-free mechanisms.

However, there are a number of applications in which

partial ("shallow") morphological and

syntactic parsing are desirable.

- Stemmers and Lemmatizers (Sub-word Morphological Parsing)

(BKL, Section 3.6; J&M, Section 3.8)

- Given a word, a stemmer removes known morphological

affixes to give a basic word stem, e.g.,

foxes, deconstructivism, uncool => fox, construct,

cool; given a word which may have multiple forms,

a lemmatizer gives the canonical / basic form of

that word, e.g., sing, sang, sung => sing.

- Stemmers and lemmatizers are used to "normalize"

texts as a prelude to selecting content words for

a text or selecting general word-forms for searches,

e.g., process, processes, processing => process,

in information retrieval.

- There are a variety of stemmers implementing different

degrees of affix removal and hence different levels of

generalization. It is important to chose the right

stemmer for an applications, e.g., if

"stocks" and "stockings" are both stemmed to "stock",

financial and footwear queries will return the same

answers.

- Part-of-Speech (POS) Tagging (Single-level Syntactic Parsing)

(BKL, Chapter 5; J&M, Chapter 5)

- Given a word in an utterance, a POS tagger returns

a guess for the POS of that word

relative to a fixed set of POS tags.

- The output of POS taggers are used as inputs to

other partial parsing algorithms (see below),

automated speech generation (to help determine

pronunciation, e.g., "use" (noun) vs.

"use" (verb)), and various information retrieval

algorithms (see below) (to help locate important

noun or verb content words).

- Existing POS algorithms have differing performances,

knowledge-base requirements, and running times

and space requirements. Hence, no POS tagger

is good in all applications.

- Chunking (Few-level Syntactic Parsing)

(BKL, Chapter 7; J&M, Section 13.5)

- Given an utterance, a chunker returns a

non-overlapping (but not necessarily total

in terms of word coverage) breakdown of that

utterance into a sequence of one or more

basic phrases or chunks, e.g.,

"book the flight through Houston" =>

[NP(the flight), PN(Houston)].

- A chunk typically corresponds to a very

low-level syntactic phrase such as

a non-recursive NP, VP, or PP.

- Chunkers are used to isolate entities and

relationships in texts as a pre-processing

step for information retrieval.

- Applications: Language Understanding (Utterance)

(BKL, Section 10; J&M, Section 17)

- When considering an utterance in isolation from its

surrounding discourse, the goal is to infer a

semantic representation of the utterance giving

the literal meaning of the utterance.

- Note that this is not always appropriate, e.g.,

"I think it's lovely that your sister and her five

kids will be staying with us for a month",

"Would you like to stand in the corner?".

- A commonly-used representation for many simple applications is First-Order

Logic (FOL) (propositional logic augmented with predicates

and (possibly embedded) quantification over sets of one or more

variables), e.g.,

- "Everybody loves somebody sometime." ->

FORALL(x) person(x) => EXISTS(y,t) (person(y) and time(t) and loves(x, y, t))

- "Every restaurant has a menu" ->

FORALL(x) restaurant(x) => EXISTS(y) (menu(y) and

hasMenu(x,y))

[All restaurants have menus]

- "Every restaurant has a menu" ->

EXISTS(y) and FORALL(x) (restaurant(x) => hasMenu(x,y))

hasMenu(x,y))

[Every restaurant has the same menu]

- The simplest utterance meanings can be built up from the

meanings of their various syntactic constituents, down to

the level of words (Principle of Compositionality (Frege)).

In this view, individual words have meanings which are

stored in the lexicon, and these basic meanings are

composed and built upon by the relations encoded in

the syntactic constituents of the parse of the utterance

until the full meaning is associated with the topmost

"S"-constituent in the parse.

- Such compositional semantics can either be done after

parsing relative to the derivation-tree or during

parsing in an integrated fashion (J&M, Section 18.5).

The latter can be efficient for unambiguous grammars,

but otherwise runs the risk of expending needless effort

building semantic representations for syntactic structures

considered during parsing that are not possible in a

derivation-tree.

- Though powerful, there are many shortcomings of this

approach, e.g.,

- Even in the absence of lexical and grammatical ambiguity,

ambiguity in meaning can arise from

ambiguous quantifier scoping, e.g., the two

possible interpretations above of "every restaurant has

a menu" (J&M, Section 18.3).

- The meanings of certain phrases and utterances in

natural language are not compositional, e.g.,

"roll of the dice", "grand slam", "I could eat a

horse" (J&M, Section 18.6)

Many of these shortcomings can be mitigated using more

complex representations and representation-manipulation

mechanisms; however, given the additional processing

costs associated with these more complex schemes,

the best ways of encoding and manipulating the semantics

of utterances is still a very active area of research.

Monday, February 16 (Lecture #8)

(FS)

- There are two types of multi-utterance discourses: monologues (a

narrative on some topic presented by a single speaker) and dialogues

(a narrative on some topic involving two or more speakers). As the NLP techniques used to

handle these types of discourse are very different, we shall treat them

separately.

- Applications: Language Understanding (Discourse / Monologue) (J&M, Chapter 21)

- The individual utterances in a monologue are woven together by two types

of mechanisms:

- Coherence: This encompasses various types of relations between utterances

showing how they contribute to a common topic, e.g.

(J&M, Examples 21.4 and 21.5),

- John hid Bill's car keys. He was drunk.

- John hid Bill's car keys. He hates spinach.

as well as use of sentence-forms that establish a common entity-focus,

e.g. (J&M, Examples 21.6 and 21.7),

- John went to his favorite musical store to buy a piano. He had

frequented the store for many years. He was excited that he could

finally buy a piano. He arrived just as the store was closing for

the day.

- John went to his favorite music store to buy a piano. It was a store

that John had frequented for many years. He was excited that he

could finally buy a piano. It was closing just as John arrived.

- Coreference: This encompasses various means by which entities previously

mentioned in the monologue are referenced again (often in shortened form),

e.g., pronouns (see examples above).

- Ideally, reconstructing the full meaning of a monologue requires correct recognition

of all coherence and coreference relations in that monologue (creating a monologue

parse graph, if you will). This is exceptionally difficult to do as the low-level

indicators of coherence and coreference (for example, cue phrases (e.g., "because"

"although") and pronouns, respectively) have multiple possible uses and are

thus ambiguous, and resolving this ambiguity accurately can be either very computationally

costly or even impossible.

- Computational implementations of coherence and coreference recognition are often forced

to rely on heuristics, e.g., using on recency of mention and basic number /

gender agreement to resolve plurals (Hobb's Algorithm: J&M, Section 21.6.1).

- Alternatively, one can weaken one's notion of what the meaning of a monologue is:

- Summarize the overall meaning of a monologue as a vector of relevant words or phrases,

where relevance is easily computable, e.g., words or phrases that are

repeated frequently in the monologue (but not too frequently ("the")).

- Summarize the most "important" meaning of a monologue in terms of the key entities

in the monologue and their relations to each other, e.g., who did what to

who in that news story?

There are a very large number of narrow NLP techniques used to access these types of monologue

meaning; they are the subject of study in the subdisciplines of Information Retrieval

(Tzoukermann et al (2003); J&M, Section 23.1) and Information Extraction (BKL, Chapter 7;

Grishman (2003); J&M, Chapter 22) respectively.

- Applications: Language Understanding (Discourse / Dialogue) (J&M, Chapters 23 and 24)

- Even if one participant plays a more prominent role in terms of the

amount speech or guiding the ongoing narrative, every dialogue is at

heart a joint activity among the participants.

- Characteristics of dialogue (J&M, Section 24.1):

- Participants take turns speaking.

- There may be one or more goals (initiatives) in the dialogue,

each specific to one or more participants.

- Each turn can be viewed as a speech act that furthers the

goals of the dialogue in some fashion, e.g., assertion,

directive, committal, expression, declaration (J&M, p. 816).

- Participants base the dialogue on a common understanding, and

part of the dialogue will be assertions or questions about

or confirmations concerning that common understanding.

- Both intention and information may be implicit in the

utterances and must be inferred (conversational implicatures),

e.g., "You can do that if you want" (but you shouldn't),

"Sylvia does look good in that dress" (and why did you notice?).

- The core of a Speech Dialogue System (SDS) is the Dialogue Manager (DM). An ideal DM should be able to

accurately discern both explicit and implicit intentions and information in

a dialogue, model and reason about both the common ground and the other

participants in the dialogue, and take turns in the dialogue appropriately.

This is exceptionally difficult to do, in large part because the domain

knowledge and inference abilities required verge on those for full AI-style planning,

which are known to be computationally very expensive (J&M, Section 24.7).

- Implemented SDS deal with this by restricting their functionality and domain of

interaction and retaining the primary initiative in the dialogue while allowing

limited initiative on the part of human users, e.g., travel management

and planning SDS (J&M, pp. 811-813).

- Alternatively, SDS can focus on maintaining the illusion of dialogue while having

the minimum (or even no) underlying mechanisms for modeling common ground or

dialogue narrative:

- Question Answering (QA) Systems (Harabagiou and Moldovan (2003); J&M, Chapter 23)

- Such systems answer questions from users which require single-word

or phrase answers (factoids).

- Given the limited form of most questions, the topic of a question can

typically be extracted from the question-utterance by very simple

parsing (sometimes even by pattern matching).

- Factoids can then be extracted from relevant texts, where relevance is assessed

using techniques from Information Retrieval and Information Extraction.

- Chatbots

- Such systems engage in conversation with human beings, sometimes with some

explicit purpose in mind (e.g., telephone call routing (Lloyds Banking Group,

Royal Bank of Scotland, Renault Citroen)) but more often just as entertainment.

- The first chatbots were ELIZA (Weizenbaum (1966): a simulation of a Rogerian

psychotherapist) and PARRY (Colby (1981): a simulation of a paranoid personality).

- ELIZA maintains no conversational state, instead relying on strategic

pattern-matching of key phrases in user utterances and substitution of

these phrases in randomly-selected utterance-frames. PARRY maintains

a minimal internal state corresponding to the degree of the system's own

"emotional agitation", which

is then used to modify selected user utterance-phrases and their

response-frames.

- There are many chatbots today, e.g.,

(see also

The Personality Forge,

The Chatterbot Collection, and

character.ai). Though many older chatbots rely on modifications

of the mechanisms pioneered in ELIZA and PARRY, modern

chatbots are often built using Seq2Seq modeling as

implemented by neural network models (Vajjala et al (2020),

Chapter 6).

- Regardless of the simplicity of the mechanisms involved, chatbots can (with the

co-operation of the human beings that they interact with) give a startling

illusion of sentience (Epstein (2007); Tidy (2024); Weizenbaum (1967, 1979)). This is due

in large part to innate human abilities to extract order from the environment,

e.g., hearing voices or seeing faces in random audio and visual noise,

which (in the context of interaction) assumes sentience and agency where

none is present.

- Current dialogue systems can give impressive illusions of

understanding (especially recently-developed

conversational AIs based on large language models such

as ChatGPT and Bing's AI chatbot (Kelly (2023))) and do

indeed have sentient

ghosts within them -- however, for now, these ghosts come

from us (Bender and Shah (2022); Greengard (2023);

Videla (2023)). Hence, these systems are

for all intents and purposes "glorified version[s] of

the autocomplete feature on your smartphone"

(Mike Wooldridge, quoted in Gorvett (2023)), conflating

the most probable as the correct, and answers

that are given to questions (in light of known problems

of these systems wrt factual consistency and citing

appropriate sources for statements made) should be treated

with extreme caution (Du et al (2024); Dutta and Chakraborty (2023)).

- Applications: Automated Language Acquisition

- Applications: Machine Translation (MT) (Hutchins (2003);

J&M, Chapter 25;

Somers (2003))

- MT was among the first applications studied in NLP

(J&M, p. 905). MT (and indeed, translation in general)

is difficult because of various deep morphosyntactic

and lexical differences among human languages, e.g.,

wall (English) vs. wand / mauer (German) (J&M, Section 25.1).

- Three classical approaches to MT (J&M, Section 25.2):

- Direct: A first pass on the given utterance directly

translates words with the aid of a bilingual dictionary,

followed by a second pass in which various simple

word re-ordering rules are applied to create the

translation.

- Transfer: A syntactic parse of the given utterance

is modified to create a partial parse for the translation,

which is then (with the aid of a bilingual word and

phrase dictionary) further modified to create the

translation. More accurate translation is possible

if the parse of the given utterance is augmented with

basic semantic information.

- Interlingua: The given utterance undergoes full

morphosyntactic and semantic analysis to create a

purely semantic form, which is then processed in

reverse relative to the target language to create the

translation.

The relations between these three approaches are often

summarized in the Vauquois Triangle:

- The Direct and Transfer approaches require detailed (albeit

shallow) processing mechanisms for each pair of source

and target languages, and are hence best suited for

one-one or one-many translation applications, e.g.,

maintaining Canadian government documents in both English

and French, translating English technical manuals for world

distribution. The Interlingua approach is best suited for

many-many translation applications, e.g.,

inter-translating documents among all 25 member states of

the European Union.

- In part because of the lack of progress, the Automated

Language Processing Advisory Committee (ALPAC) report

recommended termination of MT funding in the 1960's.

Research resumed in the late 1970's, re-invigorated in large

part because of advances in semantics processing in AI

as well as probabilistic techniques borrowed from automated

speech recognition (J&M, p. 905).

- Statistical MT uses inference over probabilistic translation

and language models.

- The translation models assess the probability of a

given utterance being paired with a particular

translation using the concept of word/phrase

alignment.

- Example #1: An alignment of an English utterance

and its French translation:

- To create the necessary probabilities (which are typically

encoded in HMM), need large large

databases of valid (often manually created) alignments.

- Fully Automatic High-Quality Translation (FAQHT) is the

ultimate goal. This currently achievable for translations

relative to restricted domains, e.g., weather

forecasts, basic conversational phrases. Current MT (which

is largely based on the statistical and, most recently, neural

network (Vajjala et al (w2020, pp. 265-268) approaches) is acceptable

in larger domains if rough translations are acceptable,

e.g., as quick-and-dirty first drafts for

subsequent human editing (Computer-Aided Translation (CAT)).

(J&M, pp. 861-862; see also BBC News (2014)) or simultaneous

speech translation.

It seems likely that further improvements will require

a fusion of classical (in particular Interlingua) and

statistical approaches.

- Potential exam questions

Wednesday, February 18

- University closed; class cancelled.

Friday, February 20

References

- BBC News (2014) "Translation tech helps firms talk business round the world."

(URL: Retrieved November 14, 2014)

- Baker, J.M., Deng, L., Khuanpur, S., Lee, C.-H., Glass, J., Morgan, N.,